As the date of the next round of meetings of the “Mechanism” Committee approaches—scheduled to take place in Naqoura on December 19—attention is once again turning to the Lebanese–Israeli border, in search of indicators that might help chart the direction of the winds: a stable truce, or an escalation whose timing is chosen by Benjamin Netanyahu.

The upcoming round will be attended by the two civilian members of the committee—the Lebanese Simon Karam and the Israeli Uri Resnik—alongside the remaining military members, and in the presence of U.S. envoy Morgan Ortagus, who has effectively come to hold the reins of this delicate track, balancing two limits: containing tension and preventing collapse.

This multi-layered dynamic turns the Naqoura meetings into more than a purely technical protocol. They have become a U.S.–UN platform aimed at stabilizing an acceptable military tempo before the end of the year, even if only on a temporary basis.

Between Holiday Calendars and Threat Deadlines

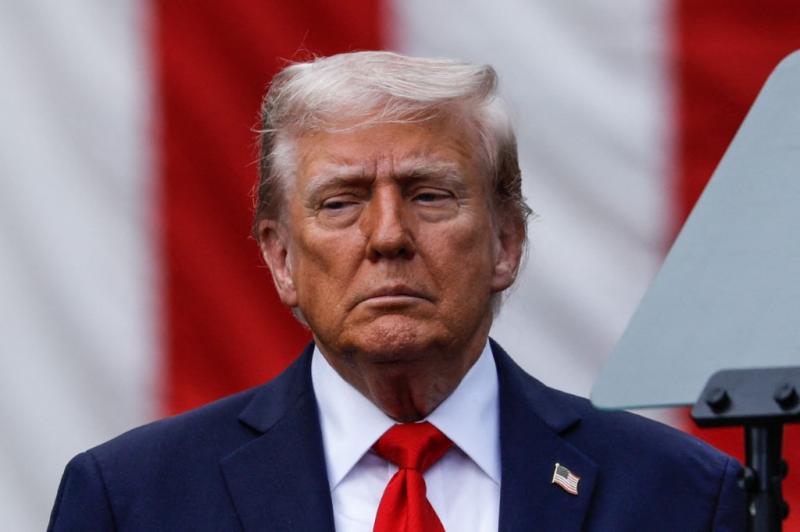

The “Mechanism” meetings come less than a week before the Christmas holiday and less than two weeks before New Year’s—precisely the timeframe that Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu had set as a deadline before moving to what he has described as a phase of “calculated escalation” against Lebanon, should what he considers Lebanon’s “evasion” from its commitment to the principle of the state’s exclusive control over weapons across all its territory continue.

Despite the controversy stirred by these threats, their timing does not appear arbitrary. Netanyahu seems intent on closing a year weighed down by political failure by imposing a new equation in the region, while Beirut is relying on U.S., European, and Arab diplomatic “mechanisms” to mitigate risks and prevent the country from being dragged into an uncalculated confrontation.

Between the Inaugural Address and the Ministerial Statement

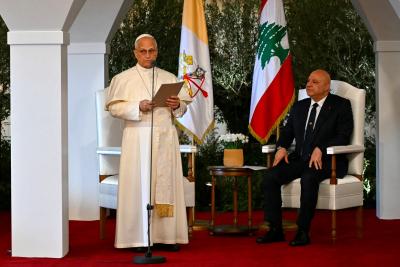

Amid these calculations, two parallel tracks have emerged domestically, forming the foundation of the state’s official position. The first is the inaugural address delivered by President Joseph Aoun on January 9, in which he explicitly reaffirmed before parliament his commitment to the principle of “exclusive state control over weapons,” without any exceptions. The second is the ministerial statement issued by Prime Minister Nawaf Salam’s government weeks later, which reiterated the same vision, enshrining the state’s monopoly over arms as a non-negotiable pillar of the institutional recovery phase.

Through this presidential–governmental duality, Lebanese legitimacy is attempting—at the very least—to entrench a theoretical framework for Lebanon’s transition into an era free of tutelage, whether Syrian or Iranian, and to close the chapter of the “parallel state” in favor of a single, unified state.

Hezbollah Between Denial of Change and Fear of the Deluge

By contrast, Hezbollah’s leadership continues to treat the positions of the Lebanese state as “slips” or “concessions” to the Israelis, in a tone that revives the rhetoric of past decades, when Lebanon was an open arena for overlapping tutelage and dual decision-making.

Yet Hezbollah’s disregard for the reality of the transformation in the structure of the Lebanese state since the beginning of this year—with all the domestic consensus and external support it entails—makes its discourse appear as though it belongs to another time, a bygone era whose regional and international realities have fundamentally changed.

The rules of the game are no longer what they once were. The Iranian cover is no longer the same in the wake of recent developments, and the Lebanese domestic mood is no longer able to endure the ongoing contradiction between the state and weapons that lie outside its authority.

Between Two Options—And No Third

Accordingly, the ultimate question becomes simple, albeit existential: Will Hezbollah seize the new Lebanese moment and take the initiative to hand over its weapons to the state, bringing an end to a four-decade-long chapter? Or will it persist in a policy of delay, pushing the country to the edge of an abyss from which no one would emerge unscathed—neither the party, nor the state, nor society?

The equation today leaves little room for gray areas. Either a single state assumes authority over decisions of war and peace, or Lebanon slides gradually toward a confrontation that most Lebanese do not want—but which may nonetheless become their fate so long as weapons remain outside the legitimacy of the state.

Please post your comments on:

[email protected]

Politics

Politics