For centuries, the Middle East has been known as a strategic passageway for the movement of people and goods. But over the past decade, the region has taken center stage in global trade strategies, with major powers seeking to make it a core hub of global connectivity. Traditional maritime routes and new overland corridors are no longer simple trade pathways; they have become arenas in a new geopolitical struggle known as infrastructure wars.

At the heart of this contest lie two international mega-projects: China’s Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), and the India–Middle East–Europe Economic Corridor (IMEC), backed by the G7, the European Union, and the United States. While both are expected to reshape global trade, instability in the Middle East may stand in the way of their full realization.

The Dragon’s Decade

Since its launch in 2013, the Belt and Road Initiative has built a vast network of infrastructure across Asia, Africa, and Europe worth trillions of dollars. The scale reflects China’s deep financial integration strategy and its long-term investments in Middle Eastern ports and energy security.

The Middle East has captured the largest share of BRI activity, especially in energy and technology. China has aligned its goals with the Gulf countries’ diversification strategies, securing major contracts in Saudi railway development, massive Iraqi oil refinery projects, and port infrastructure in the UAE.

BRI’s strength lies in its maturity, enormous scale, and centralized financing through institutions such as the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank (see Chart 1). To attract host countries, China has softened the political conditions attached to its projects.

But the initiative remains exposed to geopolitical turbulence. Although China enjoys broad maritime access, recent events in the Middle East—combined with its heavy reliance on the Suez Canal and Red Sea—have left it vulnerable to regional disruptions. The China–Pakistan Economic Corridor has also faced recurring security and financial obstacles, reducing capacity in several areas.

The Western Initiative

At the 2023 G20 Summit, a new corridor was announced: the India–Middle East–Europe Economic Corridor, presented as a transparent and sustainable alternative to BRI. In practice, it represents a strategic alliance linking India, the United States, the European Union, the UAE, Saudi Arabia, Italy, France, and Germany (see Chart 2).

The project proposes a multimodal transport network connecting Indian ports to the UAE, crossing Saudi Arabia, reaching Jordan and the port of Haifa, and extending into Europe. It also includes integrated electric grids, clean-hydrogen pipelines, and high-speed fiber-optic cables, making it a digital corridor for the 21st century (see Chart 3).

Unlike BRI’s top-down China-centered model, IMEC adopts a cooperative approach that promises shared economic benefits through high standards and local employment. For the US and Europe, the corridor offers a tool to rebalance Eurasian trade. For India, it provides critical diversification away from chokepoints and supports its “Look West” strategy to deepen engagement with the energy-rich Gulf.

Competition and Overlap

The central question is whether IMEC and BRI are rivals or complementary.

Strategically, they clearly compete. Each represents a different geopolitical axis: China and the Eurasian vision on one side, and the US-led Indo-Pacific coalition on the other. The rivalry is intensified by the India–China border dispute, China’s sensitivity to “debt-trap” accusations, and IMEC’s emphasis on sovereignty.

But in practice, the picture is more complex.

Saudi Arabia and the UAE refuse to align exclusively with either project. Instead, they aim to serve as dual hubs for both, maximizing connectivity and maximizing profits. Their ports and logistics facilities already operate within both frameworks, turning the Gulf into an unavoidable convergence point for global commerce.

Meanwhile, the persistent rivalry between Turkey and Iran has prevented regional connectivity projects from taking shape. This gives IMEC an advantage, offering a solution to a challenge BRI has been unable to overcome. Turkey’s proposed “Iraq Development Road,” linking the Gulf directly to Europe through Iraq, also factors into this shifting landscape.

Chart 1: Comparison of IMEC and BRI (Source: Author)

Chart 1: Comparison of IMEC and BRI (Source: Author)

Chart 2: Proposed Multimodal Transport Route (Source: Author)

Chart 2: Proposed Multimodal Transport Route (Source: Author)

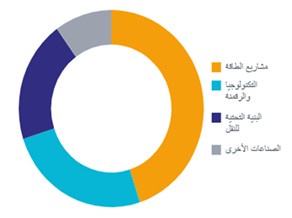

Chart 3: Investment Fields of IMEC and BRI (Source: Author)

Chart 3: Investment Fields of IMEC and BRI (Source: Author)

Instability: The Decisive Variable

Instability in the Middle East remains the primary obstacle to both initiatives, especially in the short term.

IMEC was built on a geopolitical environment shaped by the Abraham Accords, relying on political stability in the Levant. The Gaza war of late 2023 put the initiative under intense pressure and disrupted cooperation between participating states, particularly Arab countries and Israel.

BRI faces parallel challenges. Houthi attacks on commercial vessels in the Red Sea caused a sharp drop in shipping through Bab al-Mandeb and the Suez Canal. Major shipping companies rerouted vessels around the Cape of Good Hope, adding weeks of travel time and high additional costs.

The Future of Connectivity

The competition between BRI and IMEC reflects a larger shift in global power dynamics. Yet the Middle East remains the critical variable, given its control over key maritime and political chokepoints.

If wars once decided geopolitical struggles, today’s conflicts are fought with a different arsenal: diplomacy, trillion-dollar investments, and constant risk assessment. The ultimate winner will be the project that convinces global investors of its stability, its viability, and its capacity to secure future trade and supply chains.

In this new era of infrastructure wars, it is vision—not firepower—that will shape the next chapter of global commerce.

Please post your comments on:

[email protected]

Politics

Politics