For decades, "Hezbollah"’s regional weight stemmed from its military and security presence rather than political maneuvering or popular support—particularly after 2011 and the outbreak of protests in Bahrain. At the time, Manama accused the group of instigating unrest and providing training, while "Hezbollah" condemned government crackdowns on opposition forces. Relations quickly soured, with Bahrain recalling its ambassador from Beirut. Soon after, reports surfaced of "Hezbollah"’s involvement in training opposition groups in Kuwait, prompting the Gulf Cooperation Council to accuse it of threatening Gulf security. From there, tensions escalated: fiery rhetoric against Gulf states—chiefly Saudi Arabia—was matched with actions that led to sanctions on individuals and organizations suspected of ties to the party.

From Popular Sympathy to Regional Isolation

"Hezbollah"’s political activity was never taken seriously by regional authorities, who viewed it with suspicion due to its organic ties with Iran. Popular sympathy, however, peaked after the July 2006 war, when "Hezbollah"’s leader Hassan Nasrallah was elevated in the Arab imagination to a status rivaling Jamal Abdel Nasser. That image fractured after May 7, 2008, when "Hezbollah" turned its weapons inward in Beirut, and collapsed further after it intervened in Syria to fight alongside Bashar al-Assad’s regime against the opposition.

Since then, "Hezbollah"’s regional clout was tied directly to its military involvement in Syria, Iraq, and Yemen, along with security activities across multiple countries—often accompanied by accusations of undermining social stability. Its role was reinforced by the rise of the “axis of resistance,” its arsenal, and its battlefield expertise. Some states, by force of circumstance, engaged with it—not only regional actors like Qatar but also European countries such as France, which distinguished between "Hezbollah"’s political and military wings. Saudi Arabia, however, consistently rejected this approach, maintaining its stance of dealing solely with the Lebanese state.

A Role in Decline

Today, "Hezbollah" has largely lost the pillars that sustained its regional role:

- Loss of influence in Syria, once its primary arena.

- Restricted mobility abroad, even to Iran, due to tighter controls over ports, airports, and border crossings that "Hezbollah" previously bypassed under the banner of “resistance.”

- Dwindling financial resources, which once enabled its global reach.

- Disrupted military supply lines.

- The death of many first-generation commanders, who carried invaluable battlefield and security experience.

With its regional influence eroded, "Hezbollah" is being forced into its “natural size” domestically, after years of enjoying a surplus of power derived from its arsenal. Criticism of its leaders, weapons, and Iranian ties—once taboo—is now increasingly commonplace.

A Rhetorical Substitute: Dialogue with Riyadh

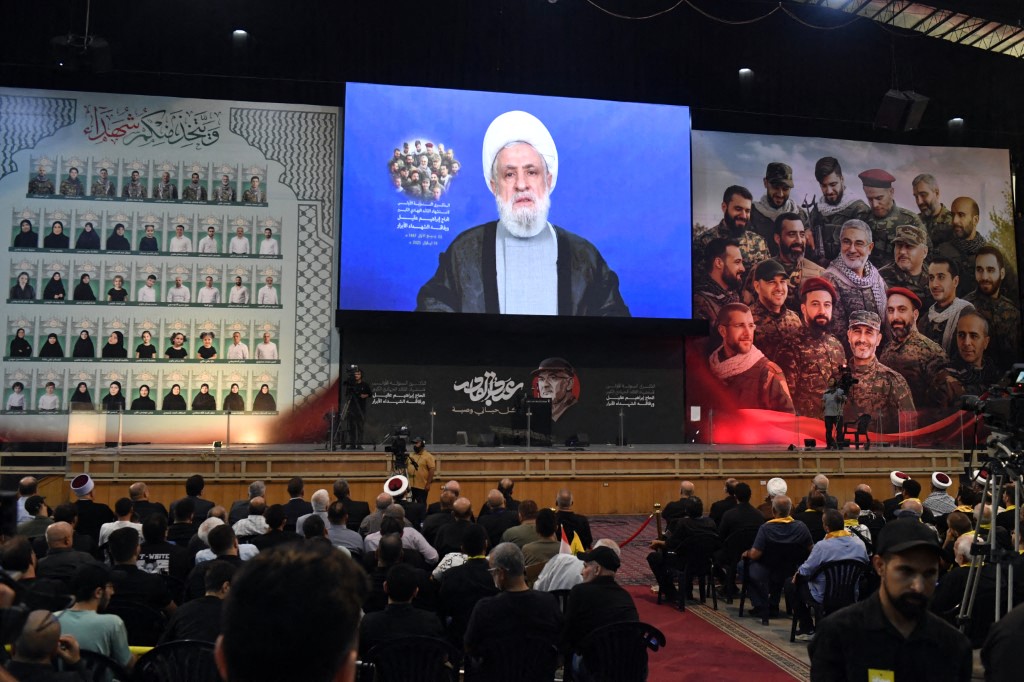

Despite acknowledging this new reality, "Hezbollah" sought a rhetorical substitute for its lost role. Deputy Secretary-General Sheikh Naim Qassem unveiled an “initiative” directed at Saudi Arabia: an invitation to “turn a new page” through dialogue that would address grievances, calm fears, and freeze past disputes, in order to confront Israel jointly.

By framing his overture as one of strength—“from a position of power and capability”—Qassem implied parity between "Hezbollah" and Riyadh, suggesting a dialogue not between state and non-state actor but between two regional players. In effect, his call amounted to an invitation for Saudi Arabia to join "Hezbollah"’s open-ended armed struggle against Israel.

The initiative, however, was dead on arrival. It primarily served to buy time and reflect Iran’s desire to project flexibility. The proposal fails both in form—emanating from a faction rather than a state—and in substance, as Riyadh has consistently insisted on dealing only with the Lebanese state. Saudi Arabia has categorically rejected "Hezbollah"’s insistence on keeping illegal arms and its doctrine of perpetual hostility toward Israel. Instead, Riyadh remains anchored in its 2002 Beirut Initiative advocating “land for peace” and the two-state solution, and it is not far removed from the momentum behind the Abraham Accords.

The Road Ahead: Two States and Two Solutions

This position was reaffirmed at the joint Saudi-French conference at the United Nations, which produced the New York Declaration. Backed by 142 UN member states, the declaration underscored the international community’s commitment to the two-state solution. Alongside growing global recognition of Palestine, this development is paving the way for that outcome.

No matter how much Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu clings to the fantasy of “Greater Israel,” the only viable way forward remains the two-state solution for Palestinians—and, in Lebanon’s case, a “two-state” solution of its own: dismantling "Hezbollah"’s “state within a state” to preserve the sovereignty of the Lebanese state itself.

Please post your comments on:

[email protected]

Politics

Politics