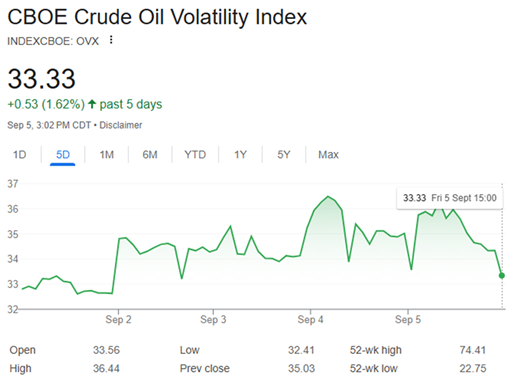

The global energy sector is in constant flux, as reflected in financial market data (see Chart 1). While renewable energy sources are gaining momentum, the world remains heavily dependent on oil and gas—both conventional and shale—with coal playing a smaller role. Investment in oil and gas continues, as investors know these sources will remain relevant for decades. Despite rapid technological advances, no alternative has proven capable of fully powering economies, especially in energy-intensive industries and transportation (such as aviation). Oil and gas therefore, remain cornerstones of global economies and critical variables in states’ geopolitical calculations.

A Strategic Chess Game

The traditional link between geopolitics and oil markets is no longer as predictable as it once was. Historically, crises between states triggered sharp increases in oil prices due to fears over supply chains (as happened after the outbreak of the Russia–Ukraine war). Today, however, multiple conflicts—including in the Middle East, the world’s primary source of oil and gas—have coincided with tumbling oil prices. U.S. crude is hovering near $60 a barrel.

This shift shows markets now respond to geopolitical shocks with greater precision, balancing global demand, non-OPEC+ supply (OPEC plus ten allied producers), and the strategic maneuvering of key players. Current low prices largely reflect concerns that supply will outstrip demand, given swelling U.S. strategic reserves.

From OPEC to OPEC+

Founded in the 1960s to coordinate oil policy among members, OPEC stabilized prices for decades until COVID-19. Rivalries over market share later sent prices plummeting, prompting the creation of OPEC+. Through voluntary production cuts, OPEC+ managed to maintain relative stability. But the group faces mounting challenges: internal divisions, U.S. pressure to boost output, ongoing wars disrupting supply chains, the rise of American shale as a dominant force in supply and demand, fluctuations in global consumption, and the near-total reliance of some members on oil revenues. These tensions threaten the bloc’s cohesion and its influence over markets.

Chart 1: Crude Oil Volatility Index (OVX) – Source: Google Finance

Chart 1: Crude Oil Volatility Index (OVX) – Source: Google Finance

The Middle East and Strategic Shifts

Saudi Arabia, OPEC+’s de facto leader and the world’s top crude exporter, is determined to preserve the group’s unity while safeguarding its own market share and maintaining prices high enough to finance Vision 2030. Riyadh views this as more than profit—it is a strategic challenge with significant risks.

The UAE, meanwhile, is pursuing its own agenda, with its national oil company investing heavily in major gas projects to diversify energy and revenue streams. Qatar, Kuwait, and Saudi Arabia are also investing in mega-projects that will soon make the Middle East the world’s second-largest gas producer, starting next year. This regional transformation adds a new strategic dimension, providing fresh income sources and securing guaranteed buyers—particularly in Europe, where demand is expected to drive new pipelines toward both European and Asian markets. Yet the success of these ventures depends on stable gas prices remaining above key thresholds.

Iran remains constrained by Western sanctions blocking its crude exports, leaving it exempt from OPEC+ quotas. Tehran has managed to keep exports afloat through “shadow fleets,” selling at discounted rates, but its facilities now require massive investment and advanced technologies still out of reach due to restrictions. Hard currency earned has gone largely into propping up the domestic economy and financing regional influence.

Simpler Calculations Outside OPEC+

Producers outside OPEC+ operate at full capacity and thus have little sway over prices, except through halting production—an option rarely in their interest. The sole exception is the United States, which, thanks to shale oil and gas, has become a decisive actor in both supply and demand.

Conclusion

Energy geopolitics in the Middle East is no longer simply about supply, demand, or episodic geopolitical tensions. It now plays out across a multi-layered chessboard of strategic calculations, economic variables, internal rifts, and external pressures. Given the absence of renewable alternatives capable of replacing fossil fuels—particularly in heavy industry and transport—the Middle East’s dominant role in the fossil fuel market is unlikely to face serious challenges in the near future.

Please post your comments on:

[email protected]

Politics

Politics