The question of exclusive state control over weapons—essentially, the disarmament of "Hezbollah"—remains locked in a web of complexity. The latest U.S.-Israeli response, rejecting the Lebanese proposals announced by President Joseph Aoun in his Army Day speech, only adds to the difficulty, placing the cabinet in a precarious position that could impact the fate of a government already divided over this sensitive file.

The U.S.-Israeli reply, delivered before the ink had dried on Aoun’s speech, insisted that Lebanon accept the American proposal brought by presidential envoy Tom Barrack as it stands. The plan calls for a clear cabinet decision setting a timetable for "Hezbollah"’s disarmament without preconditions. In exchange, Israel would commit to a ceasefire—unilaterally observed by Lebanon since its declaration on November 27 of last year—and to a simultaneous withdrawal behind Lebanon’s southern borders.

This response, which reached Speaker of Parliament Nabih Berri without securing his full approval, has raised numerous questions about its motives and timing. Many believe a cabinet decision prioritizing disarmament over a ceasefire and Israeli withdrawal is unlikely. In fact, the timing of the U.S.-Israeli message appears designed to pressure Lebanese officials into accepting disarmament first, ahead of any Israeli commitments.

Some have speculated whether Barrack’s delivery of this message was intended to block the possible return of his former colleague, Morgan Ortagus, as special envoy to Lebanon. Others suggest that another U.S. faction sent it, not to obstruct Barrack’s mission, but to signal that the weapons file has entered an extremely complex stage. Washington’s answer was swift: U.S. foreign policy remains consistent, regardless of the envoy.

In reality, a difference in approach between President Aoun and Prime Minister Nawaf Salam brought the weapons issue to the cabinet table. Aoun had included it in his inaugural address before parliament, while Salam adopted it in his government’s policy statement—making it a shared objective. Yet, they disagreed on how to address it.

President Aoun, aware early on of the sensitivity and risks of this file, initiated consultations after his election with "Hezbollah"’s leadership—sometimes directly, sometimes through intermediaries. These talks produced certain understandings. "Hezbollah" showed flexibility, which Aoun himself acknowledged on several occasions. The party’s sole condition was Israel’s commitment to the ceasefire and that the weapons issue be addressed within a domestic dialogue leading to a National Security Strategy, as referenced in both the inaugural speech and the cabinet’s policy statement.

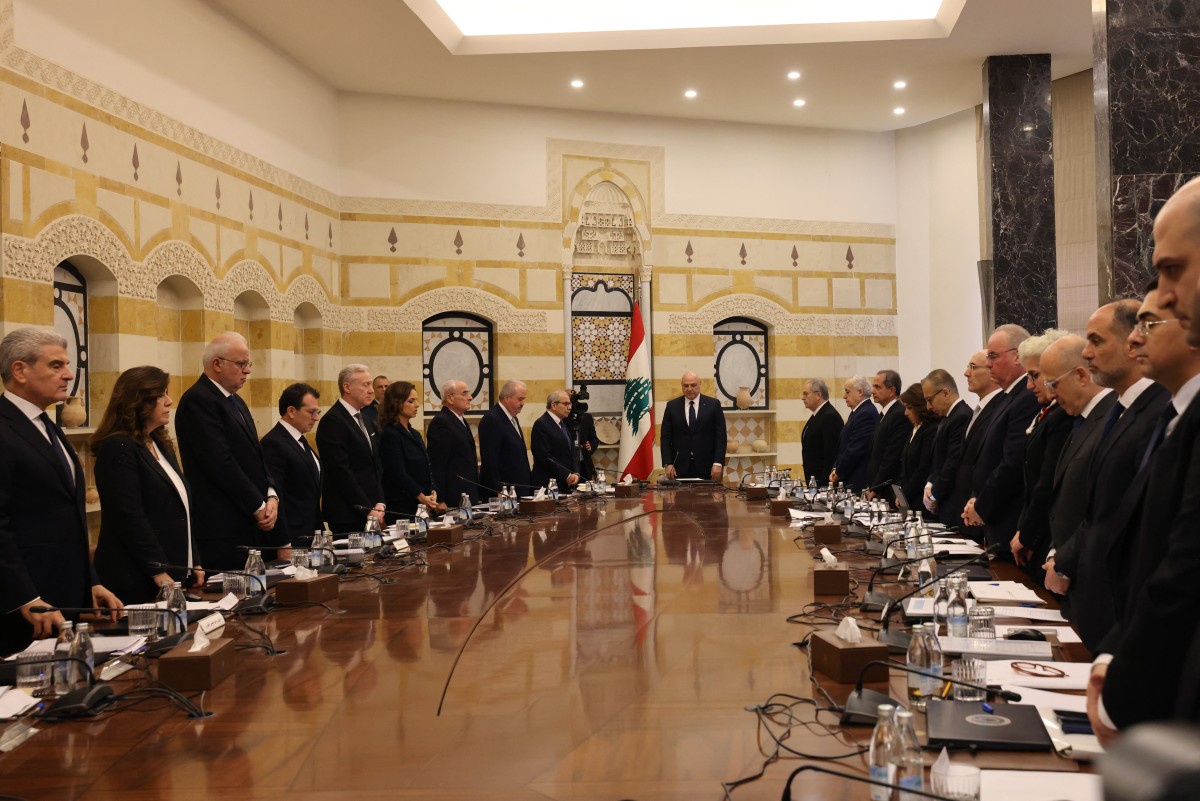

Prime Minister Nawaf Salam, however, took issue with Aoun’s solo maneuvering on the weapons issue, bypassing his role as head of government. His discomfort was fueled by close advisers who encouraged him to make his own assertive move. Thus, despite a unified Lebanese response to the American proposals—crafted jointly by the president, prime minister, and parliament speaker—Salam, with support from certain domestic political forces, proposed a special cabinet session to issue a decision on exclusive state control over weapons. This step aligned with U.S. pressure, conveyed through Barrack and other channels, urging swift action.

Regardless of what the cabinet ultimately decides, Lebanon’s unified stance remains that the country is ready to implement state control over weapons—but insists first on Israel’s commitment to a ceasefire, withdrawal behind the border, and the release of prisoners. In return, Lebanese authorities and relevant institutions would address "Hezbollah"’s weapons according to a timetable within the agreed National Security Strategy—already preliminarily endorsed by both sides—and in line with the president’s inaugural address and the government’s policy statement.

Yet, in the spirit of the saying “one man’s misfortune is another man’s gain,” the government appears to be hiding behind the weapons file—and other contentious issues—to mask its inability to deliver on promised reforms and economic recovery. Instead, it has resorted to imposing more “silent” taxes and fees, further burdening Lebanese citizens already struggling with daily hardships.

So far, the government’s achievements amount to a handful of reforms serving major political and economic interests—often aligned with foreign demands rather than domestic needs. Administrative appointments and other decisions have largely followed a “soft quota” logic. It wasted no time after passing the long-delayed law on the independent judiciary—enshrined in the Taif Accord and the constitution—before pushing through judicial appointments, in the wake of a politically charged dispute between the justice minister and the Supreme Judicial Council.

It appears this government now faces a critical test that could determine its future—with the weapons file at the center of that exam, testing its cohesion and resilience. The challenges ahead are enormous, while government capacity remains limited—particularly as the capitals and countries that supported this government have yet to translate that backing into tangible assistance. The greatest hurdle is that this support remains conditional on disarmament. Ideally, these two issues should be treated separately. But so far, they have not been.

Please post your comments on:

[email protected]

Politics

Politics