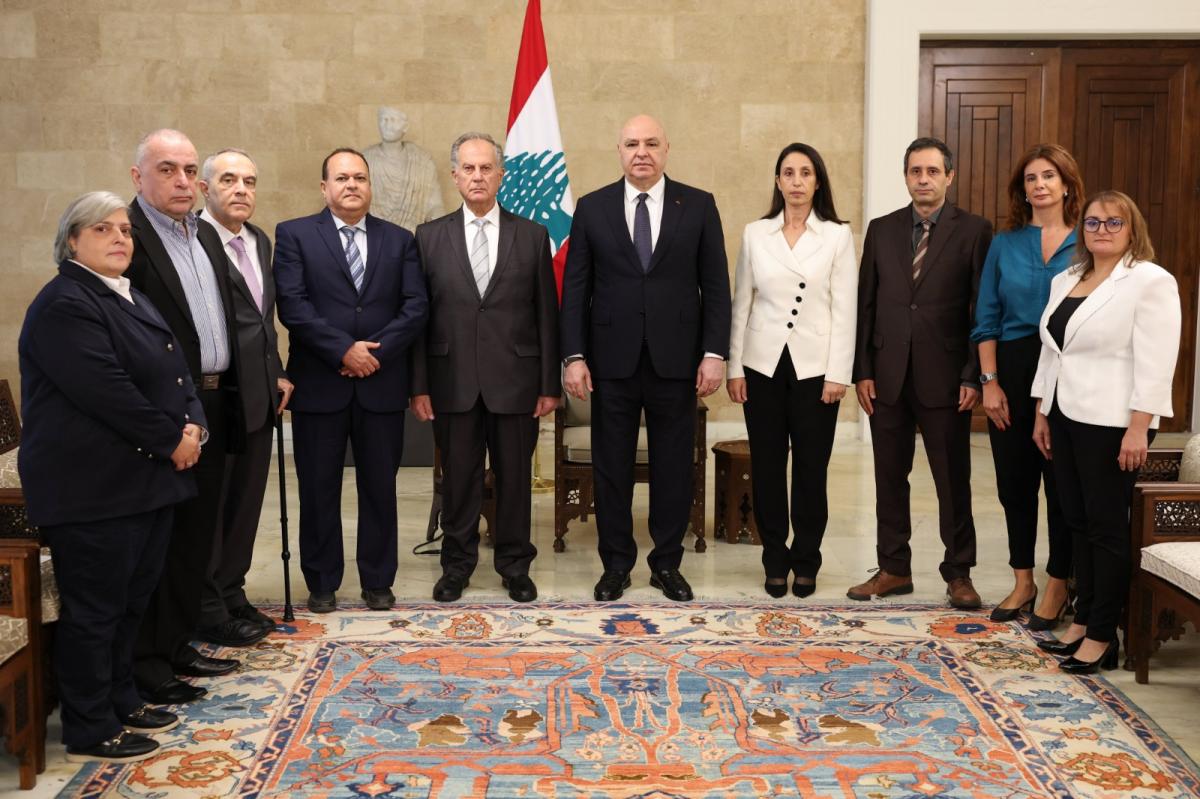

Amid the crowded political scene and its unfolding events, the news of the oath taken by members of the newly formed National Commission for the Missing and Forcibly Disappeared at The Presidential Palace in Baabda passed largely unnoticed—even though their cause remains one of the lingering wounds of Lebanon’s wars, still bleeding half a century later.

True, this official body is not the first to be established with the aim of clarifying the fate of the missing and forcibly disappeared, but it marks an important step—especially after the fall of the Assad regime, long held responsible for the disappearance of hundreds, whether in its prisons or beneath Syrian soil. To this day, even after Ahmad al-Sharaa and his followers took power in Syria, the truth remains concealed, despite Syria’s official outreach to Lebanon to address the matter of Syrian prisoners held there.

It is widely agreed that around 17,000 people remain missing, not counting the wave of kidnappings that once plagued the country, when victims were treated as lucrative prey for extortion. The Lebanese army and security agencies eventually dismantled these gangs, once the political leadership—though belatedly—resolved to act. Still, historian Dima Zein Duclerc questioned the accuracy of that figure, estimating the number to be only a few thousand at most.

The forcibly disappeared, however, number in the hundreds. Many were held in Syrian prisons—some briefly released under the Assad regime—while others lie buried in Lebanon, executed by their captors during the war but long assumed to be in Syrian jails. Such was the fate of seven out of eleven soldiers who fell during the battles of October 13, 1990; their remains were discovered years later in a mass grave on Defense Ministry grounds.

The committees formed by successive governments since the late 1990s have proven futile. Neither the much-vaunted “special relations” and “unity of path and destiny” during the Syrian occupation of Lebanon, nor the subsequent diplomatic exchanges between Beirut and Damascus after its withdrawal, managed to shed light on the fate of the missing. Even the media frenzy around prison raids in Syria under the new regime failed to produce any answers.

There has been much talk of mass graves in Lebanon. Yet whenever calls were raised to exhume it, the issue was politicized, as it is usually done with sensitive matters. Some warlords even admitted to ordering or knowing of executions. Reports in the hands of security agencies allegedly document many such graves, but opening that file remains fraught with risk, as it implicates figures in official positions and factions represented in both past and present governments.

And yet, a protest tent—perhaps the longest sit-in in Lebanon’s history—stood for years in Gibran Khalil Gibran Square outside the ESCWA building in Beirut. It kept the issue alive, thanks to committees free of political agendas and to families whose tears for their missing loved ones have yet to dry.

Out of respect for those tears, and to ease the conscience of anyone who knows the truth yet conceals it, I personally proposed a solution during a mass sit-in at that tent—broadcast live by a local TV station. I had previously shared the idea with several parties, but it was never acted upon until I recently heard a lawmaker adopt it, presenting it as draft legislation in Parliament and announcing it as a solution to this long-standing tragedy. Whether or not credit was given is beside the point.

My motivation for this proposal came from what I saw with my own eyes two days after the fall of Karantina in January 1976. I was with a friend and a group of young Armenians when a bearded man operating a bulldozer dug two massive pits. Into them were dumped heaps of charred bodies, piled atop one another. The pits were then covered with earth, and a small roller leveled the ground.

The solution I suggest is simple. It should not embarrass any of the parties or militias that fought the war and committed atrocities. Rather, it should help the political leadership achieve a positive step that could offset the many failings of the past.

It begins with a straightforward mechanism: the creation of a mailbox—physical or electronic. Anyone who was killed during the war, participated in a killing, witnessed one, buried a victim, or knows a burial site could anonymously send a message revealing what they know. This would allow those haunted by guilt to unburden their consciences.

Now that the National Commission for the Missing and Forcibly Disappeared has been formed, it should work with experts, judges, security officials, victims’ committees, humanitarian organizations, and DNA specialists. Messages received should be referred to the commission, investigated thoroughly, and verified on the ground. This would mark the first step in a long journey to reveal hidden truths and end the torment of the victims’ families.

A perpetrator silenced by party loyalty may still find the courage to confess anonymously in writing—an act akin to repentance or atonement. For the authorities, this would be a noble humanitarian step, uncovering truths that might otherwise remain locked in memory or buried underground.

Even the missing themselves—though dead—would rest easier, as their families’ long vigil would finally yield truth. Many names would be known again, no longer listed as missing, allowing families to bury their remains and resolve long-pending matters of inheritance, property, and identity.

It is a practical proposal, offered amid the overwhelming political, security, economic, social, and electoral distractions—both regional and international. But the question remains: who will adopt it?

Please post your comments on:

[email protected]

Politics

Politics