In a surprising move that could have strategic implications for Lebanon’s internet landscape, American entrepreneur Elon Musk contacted the Lebanese President to express his interest in introducing Starlink to the Lebanese market. This development, arriving at a critical moment, reignites debate over the future of the country’s telecom sector, digital sovereignty, and the role of the state in an age of technological globalization.

Since Lebanon’s independence, no legal or official precedent has allowed any local or foreign private entity to connect services directly to international networks without going through state-controlled gateways. Legislative Decree No. 126, issued on June 7, 1959, granted the Lebanese government exclusive rights to establish, invest in, and operate international telecommunications networks. This monopoly has remained intact—even during the country’s worst financial crises and the collapse of state institutions—and has not been legally breached to date.

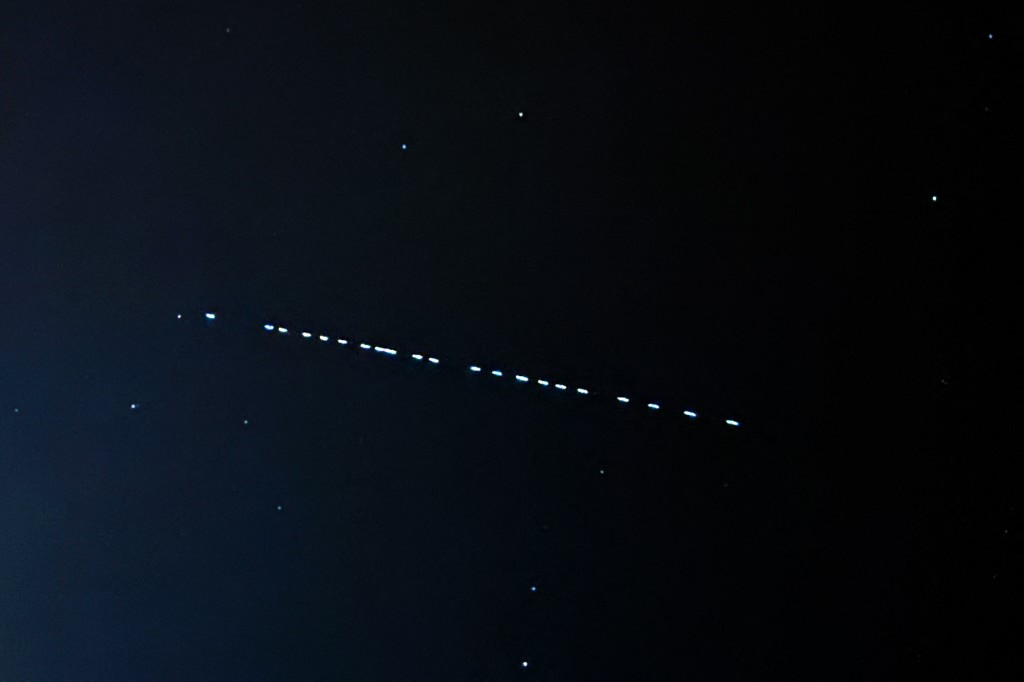

However, Starlink’s technology challenges this traditional legal framework. The service allows users to connect directly to satellites via small devices, sending signals from a dish mounted on the user’s rooftop into space, then down to a ground station in a foreign country, and finally into the global internet—completely bypassing the Lebanese state’s gateways operated by the Ministry of Telecommunications or the Ogero public company. In essence, Starlink enables a form of “sovereign internet” for users, one that is practically immune to direct Lebanese oversight, raising highly complex legal questions.

From a constitutional standpoint, granting such a license under current conditions could be considered invalid and subject to annulment by Lebanon’s State Council. That’s why legal experts and observers argue that the solution isn’t to bypass the law, but rather to issue a modern legal framework through Parliament—one that keeps pace with technological advances, regulates satellite internet, preserves national interests, and clearly defines sovereignty boundaries and state rights. Such a framework would also establish surveillance mechanisms, organize fees, designate oversight authorities, and guarantee cybersecurity protections.

Legal objections aren’t the only hurdles facing Starlink. Traditional internet service providers (ISPs and DSPs) in Lebanon have publicly voiced their opposition to Starlink’s entry, warning of subscriber losses, tax inequality, and risks to the domestic infrastructure they’ve invested in over many years. Still, several industry experts view these concerns as exaggerated. Satellite internet remains relatively costly compared to terrestrial services and is primarily targeted at underserved or remote regions, making it more complementary than competitive.

Looking abroad, other countries have adopted a variety of approaches to satellite internet. In France, for instance, the Council of State revoked Starlink’s license in 2022 after civil society groups challenged it on environmental and competition grounds. The European Union has gone further, launching its own sovereign initiative—IRIS²—to strengthen “digital independence” and reduce reliance on U.S. companies. On the other hand, countries like the UAE have taken a more flexible stance, while maintaining tight regulatory control and asserting state ownership over all international gateways.

Lebanon now finds itself at a sensitive crossroads. On one side lies the real potential to benefit from a cutting-edge service that could alleviate connectivity challenges, especially in rural or infrastructure-poor regions. On the other lies the pressing need to uphold state sovereignty over cross-border data flows and to enact a clear legal framework ensuring transparency and public interest.

In a formal statement, Minister of Telecommunications Charbel Haj affirmed that the ministry does not submit any draft decisions or decrees to the Cabinet without consulting the relevant legal authorities, stressing that the Starlink file will be no exception. This indicates an institutional intention to manage the issue carefully and gradually within official channels.

The bottom line: Starlink’s entry into Lebanon is not merely a technological development—it’s a political, economic, and legal turning point. The answer isn’t blind acceptance or outright rejection, but rather the urgent need to legislate a clear framework. One that defines the state’s relationship with emerging technologies and shields Lebanon from digital chaos, it is ill-equipped to handle it amid national collapse.

Please post your comments on:

[email protected]

Politics

Politics