U.S. presidential envoy Thomas Barrack is returning to Lebanon to receive its response to the plan he proposed for disarming “Hezbollah” and implementing reforms in exchange for Israel’s withdrawal from occupied Lebanese territories and the provision of aid.

Today, Lebanon faces one of two scenarios: either to accept the plan as is or to reject it and face the consequences. But what would those consequences be if Lebanon says no?

The Proposed Roadmap

The American paper outlines a roadmap built around three main pillars:

First Pillar – Disarmament of non-state factions and groups: This is the core requirement on which all other elements hinge, including international aid for Lebanon.

Second Pillar – Implementation of financial, economic, and security reforms: These include border control and anti-smuggling measures, restructuring the banking sector, addressing public debt and public administration, budget reform, limiting the cash economy, and combating financial crimes and corruption.

Third Pillar – Improving relations with Syria: By enhancing political and security ties, asserting border control and demarcation, and increasing economic cooperation.

In exchange for Lebanon’s commitment to these demands, funds would be provided to support reconstruction and to stop Israeli aggressions—under the guarantee of the United States, which would oversee Lebanese-Syrian, Syrian-Israeli, and Lebanese-Israeli contacts.

The Carrot and And the Stick

The American plan follows the classic “the carrot and the stick” approach. It is unlikely that Lebanon will outright reject it, as the repercussions could span military, economic, and political realms:

Renewed military escalation with Israel, which would result in the displacement of southerners from their homes, risking increased youth emigration and devastating Lebanon’s economy—especially if escalation becomes severe enough to prompt a complete blockade, all the more dangerous since Syria is no longer a reliable backdoor for smuggling as in the past.

Escalation with Israel or Syrian factions along the eastern border would inevitably weaken the government and its institutions due to political and security instability, leading to a suspension of international aid, the withdrawal of investments, and a halt to economic recovery.

Deepening the economic crisis and increasing Lebanon’s isolation by blacklisting it in November—coinciding with the deadline for implementing the plan. This would sever Lebanon’s ability to import and fully disconnect it from the global banking system, triggering catastrophic economic, financial, and social consequences, including a halt to reconstruction aid.

Hunger resulting from a blockade would turn Lebanon into a battlefield for internally fueled, externally funded conflicts, effectively rendering it a failed state.

A Composite Index to Measure Multi-Dimensional Risks

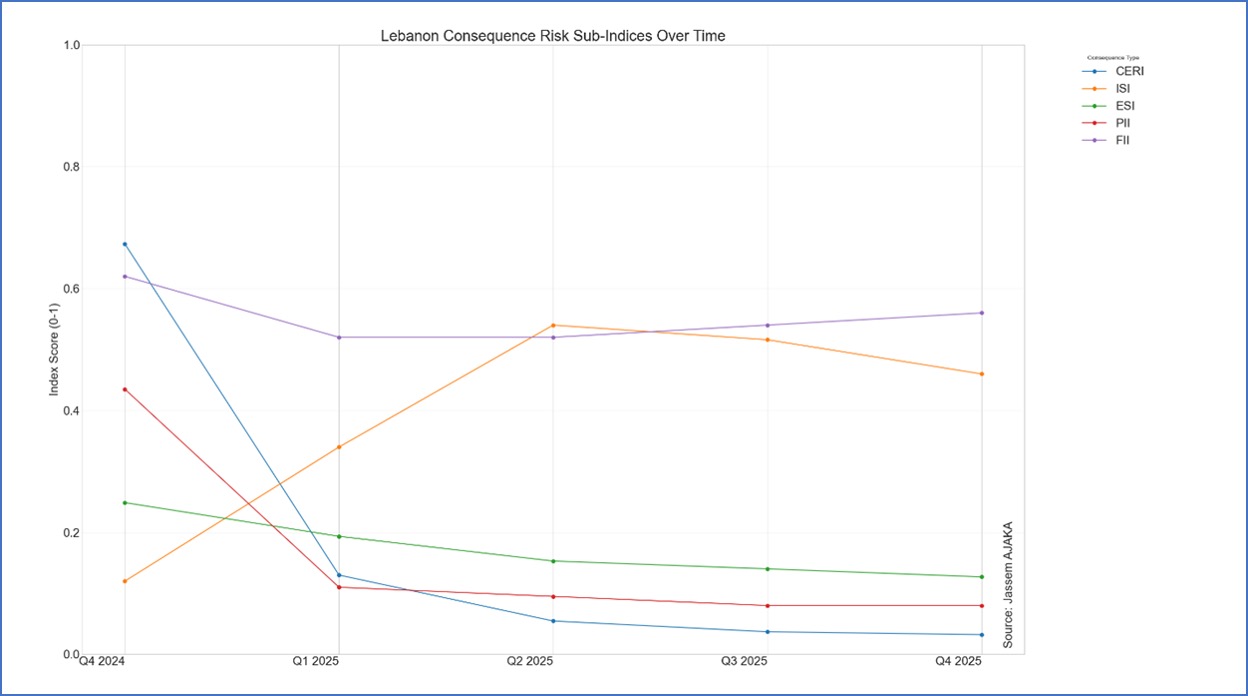

Assessing Lebanon’s multi-dimensional risks at this stage is challenging due to many unavailable data points. To address this, we have developed a composite index to track and measure these risks, built on five key indicators:

Conflict Escalation Risk Indicator (CERI): Measures the likelihood of renewed conflict through sub-indicators like border incidents, civilian casualties, displaced populations, and material damage (0: very low probability, 1: very high probability).

International Support Indicator (ISI): Gauges the level of international financial and diplomatic support based on sub-indicators like aid, sanctions, diplomatic engagement, and especially UNIFIL’s mandate renewal in southern Lebanon (0: strong support, 1: no support).

Economic Stability Indicator (ESI): Reflects the health and resilience of the economy, measured by economic growth, inflation, foreign direct investment, foreign currency reserves, and public debt (0: fragile economy, 1: stable economy).

Political Instability Indicator (PII): Captures challenges to government stability, political divisions, and social unrest through factors like government lifespan, disruptions, and security incidents (0: political stability, 1: political instability).

Foreign Interference Indicator (FII): Tracks the degree of foreign involvement threatening the country’s sovereignty and stability through external military presence or activity, arming local factions, and diplomatic pressure (0: no external interference, 1: significant interference).

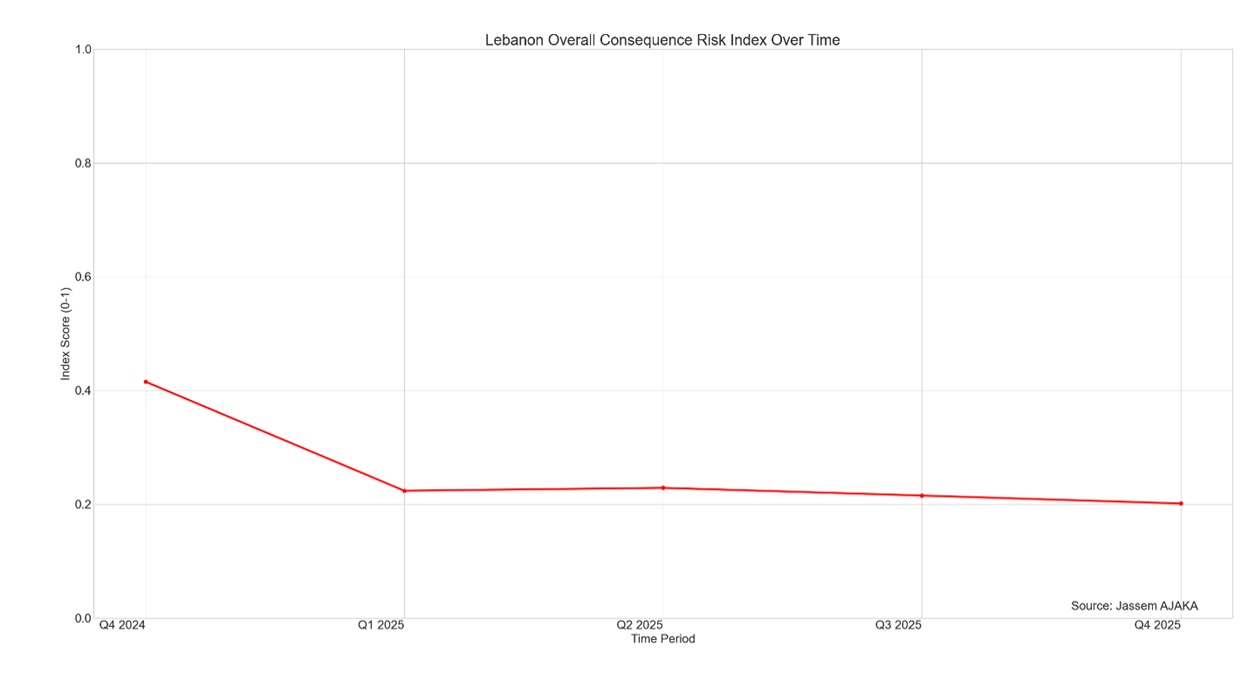

These sub-indicators are then integrated into the overall Lebanon Crisis Risk Index (LCRI), which ranges from 0 (lowest risk of consequences) to 1 (highest risk of consequences).

Major Challenges Ahead

Our simulated indicators show that risk levels have declined compared to early 2024, thanks to the election of a president, the formation of a new government, key appointments such as the army commander and central bank governor, and renewed international and Gulf engagement with Lebanon (see Chart 1 and Chart 2).

Chart 1: Indicators measuring and tracking multi-dimensional risks (Source: Author’s calculations).

Chart 1: Indicators measuring and tracking multi-dimensional risks (Source: Author’s calculations).

Chart 2: Overall index measuring and tracking multi-dimensional risks (Source: Author’s calculations).

Chart 2: Overall index measuring and tracking multi-dimensional risks (Source: Author’s calculations).

Despite this decline—bringing risk levels to the “moderate to high” category—the overall risk remains far from low enough to rule out another surge. Any security or military incident could quickly raise the overall risk level, shaking Lebanon’s security, social cohesion, or economic foundations. The most sensitive among these indicators is the risk of Lebanon’s isolation from the financial system by being placed on the blacklist.

In conclusion, Lebanon faces immense challenges that could drag it back to the Middle Ages if it fails to implement the reforms and corrective measures demanded by the international community, especially the United States. The crucial question is: will Lebanon’s response align with international expectations, or are we heading toward chaos and isolation threatening the very fabric of the Lebanese state?

Please post your comments on:

[email protected]

Politics

Politics