In the aftermath of World War II, the victorious Allied powers met in Potsdam, Germany, to lay the foundations for peace in Europe and to shape the new world order. Yet this conference, intended as a moment of consensus, actually marked the beginning of a long confrontation between the Western powers and the Soviet Union: the Cold War.

A setting full of symbolism

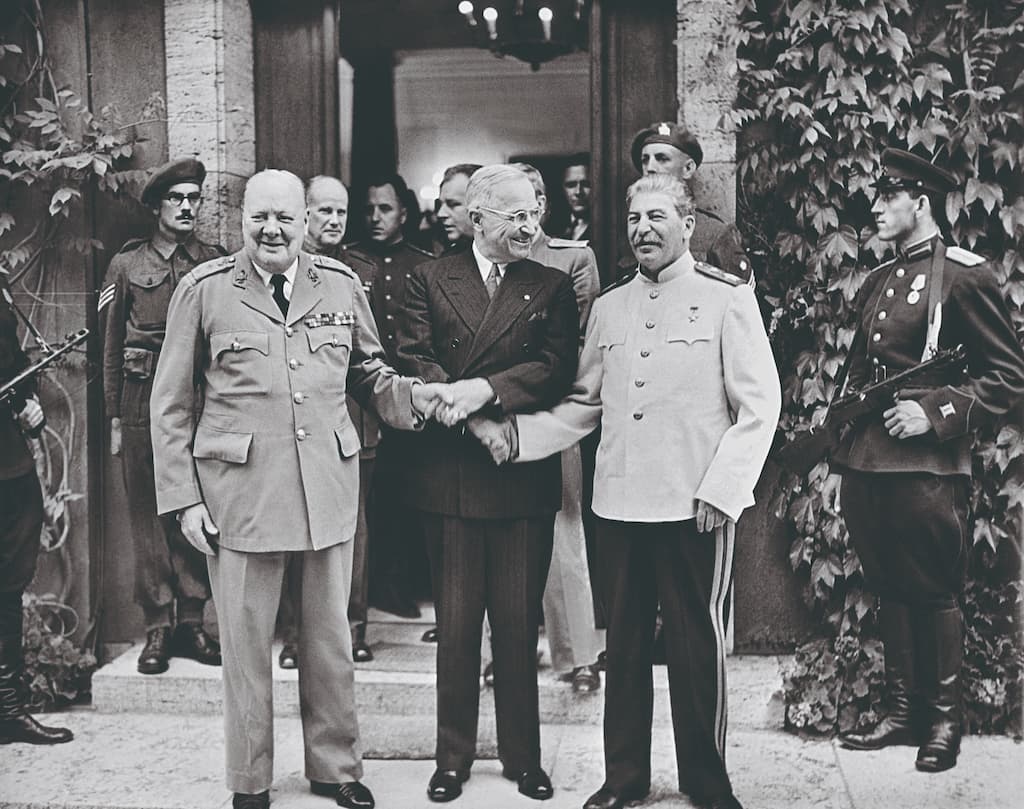

The conference opened on July 17, 1945, in Cecilienhof Palace, the former residence of the Crown Prince of Prussia, located in the Soviet occupation zone. Picturesque but surrounded by ruins and swarming with mosquitoes, the site became, for two weeks, the stage for intense negotiations between the three main victors of Nazism: the United Kingdom, the United States, and the USSR.

Winston Churchill initiated the conference. As early as May 6, even before Germany’s surrender, he proposed a meeting to Harry Truman, the new U.S. president, to plan for the postwar period. Charles de Gaulle, though leader of one of the liberating nations, was excluded from the talks, a decision he strongly condemned.

A climate of growing mistrust

Churchill was worried about Soviet advances in Eastern Europe. He accused Stalin of imposing communist regimes wherever the Red Army had passed. He was also concerned about Truman’s inexperience, seeing him as too idealistic. In a letter, he wrote: “An iron curtain has descended across the Soviet front.”

Truman arrived in Germany only on July 15. He met Stalin on July 17, describing him as “extremely polite” but manipulative. The cordial surface barely masked deep differences. The conference began that day, chaired by Truman at Stalin’s suggestion.

Difficult negotiations

Key issues included the fate of defeated Germany, the reconstruction of Europe, the USSR’s entry into the war against Japan, and the question of reparations.

Initial consensus on Germany — no central government for now, demilitarization, denazification, and continued occupation zones — quickly gave way to major disagreements.

Stalin demanded heavy reparations to compensate for the USSR’s wartime destruction. But the Anglo-Americans, wary of repeating the Versailles Treaty’s mistakes, refused to weaken Germany to the point of fostering resentment. Another point of contention was Poland. Stalin wanted to install a pro-Soviet government, which the Western powers opposed, though they failed to prevent it.

Atomic secrecy and the shadow of a new balance

During the conference, Truman received crucial news: on July 16, the U.S. had successfully tested its first atomic bomb in the New Mexico desert. This changed the strategic balance. He informed Churchill on July 18 but gave Stalin only vague information. Stalin, though surprised, remained calm and didn’t reveal that his intelligence services were already aware of the test.

This new weapon gave Truman a sense of superiority that shaped his stance in the negotiations. In private letters, he wrote: “I have some aces up my sleeve.”

Spheres of influence and realpolitik

The conference cemented the idea of spheres of influence, though never explicitly stated. Eastern Europe fell under Soviet control, while Greece, Spain, and Italy remained in the Western camp.

Germany was divided, and the Polish border was shifted west to the Oder-Neisse line, allowing Poland to reclaim land at Germany’s expense, in compensation for territories annexed by the USSR.

Churchill, weakened while awaiting the results of British elections, hoped to regain control. But on July 26, he was replaced by Labour leader Clement Attlee after a major electoral defeat. Attlee, lacking charisma and political weight, left the stage to Truman and Stalin.

An outward peace, a latent war

The conference ended on August 2. Officially, the three leaders pledged to build “the conditions for lasting peace in Europe.” But behind the forced smiles, deep disagreements and tacit arrangements laid the groundwork for a systemic rivalry between two worldviews: capitalist and democratic in the West, communist and authoritarian in the East.

In his memoirs, Truman described the meeting as “a tough showdown” and concluded: “The Soviets understand only one thing: force.” This belief would guide U.S. foreign policy for decades to come.

A historic turning point

The Potsdam Conference was a pivotal moment: the official break-up of the victors’ alliance.

While the victory over Nazism could have led to a truly collaborative peace, divergent interests, mutual distrust, and geopolitical ambitions planted the seeds of the Cold War.

Potsdam, more than an epilogue to World War II, was in fact the prologue to a new global confrontation — one that would last nearly half a century.

Please post your comments on:

[email protected]

Politics

Politics