Despite being relatively water-rich compared to its arid neighbors, Lebanon suffers from chronic water mismanagement and distribution inefficiencies. A staggering 85% of its surface water flows directly into the sea—untapped—due to insufficient storage infrastructure.

A Water-Rich Country in Crisis

Pre-2019 statistics reveal that the average Lebanese citizen consumed between 700 and 1,000 cubic meters of water annually. Yet, the country fails to capitalize on its natural water endowment because of administrative disarray, crumbling infrastructure, and a lack of strategic planning.

The First Failure: Administrative Mismanagement

Reforming Lebanon’s water sector requires a holistic, sustainable approach that tackles institutional, technical, financial, and environmental dimensions.

At the heart of the dysfunction is fragmented governance. Since 2000, water management responsibilities have been split among the Ministry of Energy and Water and four regional water establishments—Beirut & Mount Lebanon, North Lebanon, South Lebanon, and the Bekaa. This divided authority has created overlapping jurisdictions, poor coordination, and the absence of a unified national water strategy.

A key step toward reform would be consolidating governance under a single reference authority, empowering municipalities to participate through decentralized water management models, and implementing transparent, accountable human resource practices. Proper oversight of contracts and imported technical systems—from pumps to spare parts—is essential.

Legislation, such as Law 77/2018 governing water rights and resource usage, remains largely unenforced. Municipalities must also be tasked with protecting water basins by preventing encroachments and implementing environmental regulations.

The Second Failure: Aging Infrastructure

Lebanon’s water network, much like its electricity grid, is dilapidated and outdated. Many pipes date back to the French Mandate era, rendering them unfit for modern distribution needs. In some regions, water loss due to leaky pipes exceeds 40%.

Revitalizing the system requires replacing decaying pipes and extending networks to underserved areas. Moreover, while new dams have been built, they remain insufficient. Additional dams and groundwater reservoirs are needed, especially in drier zones.

Equally urgent is the construction and modernization of water treatment plants—including seawater desalination facilities for industrial and potentially agricultural use.

The Third Failure: Lack of Data and Research

Lebanon lacks comprehensive water studies to inform planning. With a population swollen by refugees—whose water consumption is estimated at double the national need—there is an urgent need for a nationwide survey of surface and groundwater resources, usage levels, and extraction patterns. Only then can a sustainable water management model be developed.

The Fourth Failure: Financing, Billing, and Social Equity

The sector relies on two funding sources: external (for system setup and infrastructure) and internal (for operational costs, maintenance, and salaries). Lebanon’s historical reliance on international donors such as the World Bank, the EU, and UN programs is not sustainable without internal reforms.

Domestically, water pricing has soared—doubled in dollar terms—yet remains opaque and unaccountable. Consumers are billed annually, in lump sums, without consumption-based calculations.

Introducing water meters could make billing fairer and promote conservation. However, this necessitates a stable water pressure system, which would eliminate the need for personal water tanks—often responsible for spillage and building hazards.

Awareness campaigns must encourage timely bill payments and customer feedback. At the same time, instilling a culture of water sustainability and training new generations of engineers is vital.

A Technological Leap Forward

Lebanon's water sector still operates with technologies dating back to the French Mandate. A 21st-century overhaul is long overdue. Modernization demands advanced leak detection systems, digitized consumption tracking, and predictive maintenance. Automation and digital billing systems would help curb corruption and increase revenue collection.

A water sector of this importance deserves to be led by a highly qualified, apolitical engineer—guided solely by science, national commitment, and ethical integrity.

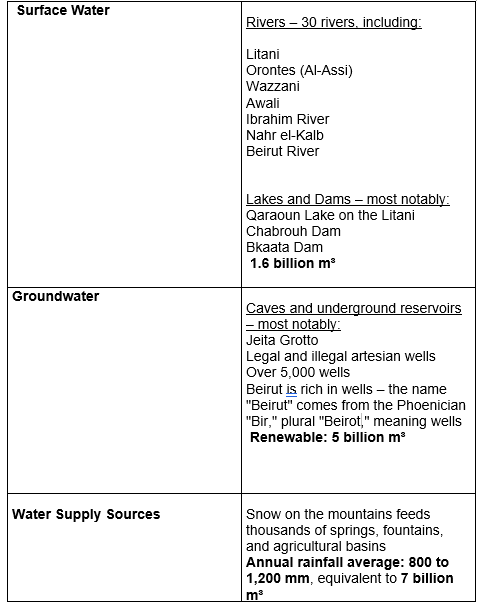

Lebanon’s Water Resources: A Snapshot

The following charts offer an overview of Lebanon’s water resources, usage distribution, and the major challenges it faces.

Key Challenges

- Lack of Storage: Insufficient dams and reservoirs lead to rainwater waste.

- Contamination: Sewage leaks into rivers and groundwater.

- Industrial Pollution: Factories discharge chemicals into rivers or landfills that seep into water sources.

- Illegal Extraction: Widespread use of unauthorized wells depletes aquifers.

- Soaring Demand: Driven by population growth and refugee influx.

- Climate Change: Longer droughts and irregular rainfall patterns.

Potential Solutions

In response to this crisis, Lebanon can adopt short-term solutions with long-term potential. These include:

- Recycling treated wastewater for agriculture

- Seawater desalination along the coast

- Rainwater harvesting in sterilized tanks at homes, schools, and factories

- Interconnecting water supply networks between regions

Lebanon’s water crisis is not one of scarcity—but of systemic neglect. With political will, engineering vision, and community participation, this essential resource can once again serve as a pillar of national resilience.

Please post your comments on:

[email protected]

Politics

Politics