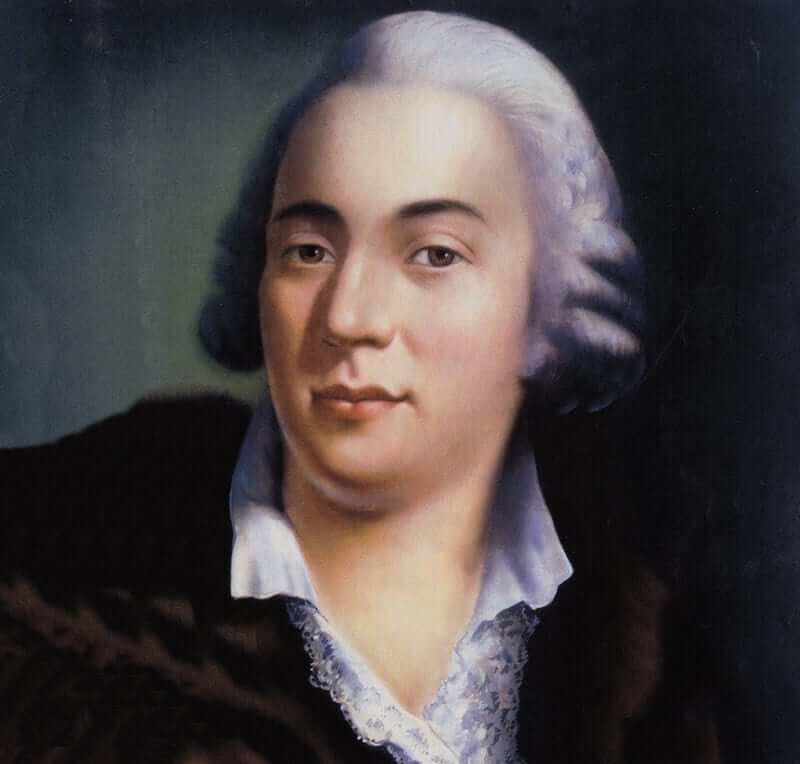

In European memory, certain names go beyond being mere historical figures and become cultural symbols. One of these names is Giacomo Casanova, the man whose name has become synonymous with the seducer, a constant reference in the literature of lovers and deceivers.

But who was Casanova really? Was he just a womanizer, a wandering philosopher, a clever adventurer, a trickster, or a brilliant writer living in the tension between pleasure and reason?

Casanova was born in 1725 in the Italian city of Venice to a modest family working in the theater. From an early age, he showed notable intellectual and artistic inclinations. He learned Latin and Greek, studied law, and was soon drawn to the allure of adventure and travel across Europe’s capitals.

His fame wasn’t built solely on philosophical lectures or his writings, but especially on his sensational autobiography, The Story of My Life, in which he detailed his emotional and intellectual adventures with enticing, surprising vividness.

Contrary to the superficial image often captured in the phrase “the Casanova of his time,” he wasn’t just a reckless or shallow lover. His writings and letters reveal that he saw human relationships as a complex art, based on intelligence, wit, cunning, persuasion, and an understanding of human nature. He didn’t seduce women with beauty or wealth, but with personal charm, vast knowledge, and captivating speech. His conversations resembled debates, and his relationships were filled with intellectual paradoxes and deeply human moments.

Throughout his life, Casanova took on many roles, he was a priest for a time, a professional gambler, a diplomat, and a Machiavellian-style political trickster. He was arrested in Venice for “crimes against morality and religion,” and his legendary escape from the Doge’s Palace prison added a heroic dimension to his myth, symbolizing boldness and courage.

Later, he formed connections with thinkers like Voltaire and wrote on philosophy, science, and politics, engaging with topics such as individual freedom, religion, and identity. This made him one of the intellectuals of his era, not merely a fleeting lover.

Casanova died in 1798, alone, in a remote castle in Bohemia (now the Czech Republic), where he worked as a librarian for a nobleman. It was there, during his final years, that he wrote his memoirs.

Casanova was likely more than just a womanizer. He was a man who lived life’s contradictions, feared loneliness, and moved in a world of masks, yet insisted on writing truthfully, so that he might live on.

Please post your comments on:

[email protected]

Politics

Politics