Is There a Government Plan to Tackle Lebanon’s Looming Drought Crisis?

Lebanon is currently experiencing one of its driest years in recent memory—a situation meteorologists describe as part of an ongoing climate anomaly that began around 2015. Rainfall levels have dropped to nearly 50% below average, raising alarms ahead of a potentially harsh summer season. But the water shortage is only the tip of the iceberg, revealing deeper, systemic problems in Lebanon’s water sector.

A Broken Water System

At the heart of Lebanon’s water crisis lies mismanagement. Decades of neglect and a lack of investment have eroded the country's water infrastructure, leaving it incapable of proper storage or maintenance. Experts estimate that up to half of Lebanon’s water supply is lost due to leakage in the decaying pipeline network. This directly impacts household access to water, as evidenced by government data pointing to sharp declines in water distribution.

But it’s not just poor infrastructure. Corruption is a major factor, with collusion between private water truck operators and those overseeing regional water facilities. Add to that the absence of proper sewage systems, poor solid waste management, and the rapid spread of residential construction into mountainous areas—and the result is widespread pollution of natural springs and a drop in accessible groundwater reserves.

To make the problem worse is climate change. Lebanon’s four seasons have grown increasingly unpredictable, particularly in terms of rainfall. Rising temperatures are leading to further depletion of groundwater, the drying up of rivers, and the evaporation of surface water exposed to sunlight. The situation has been further strained by the influx of Syrian refugees, which has more than doubled national water demand. Many among these populations are now forced to rely on unsafe drinking water.

Water Consumption by the Numbers

According to Lebanon’s national water strategy, total water demand in 2010 stood at around 1,473 million cubic meters, with individual consumption averaging 180 liters per day. This was broken down into:

810 million m³ for agriculture

152 million m³ for industry

6 million m³ for tourism

By 2020, total demand had decreased to 1,232 million cubic meters, with average individual consumption dropping to 125 liters per day. Yet the breakdown shifted significantly:

882 million m³ for agriculture

350 million m³ for industry

350 million m³ for tourism

These figures, however, are subject to scrutiny. The lack of effective monitoring, combined with a deteriorating infrastructure, casts doubt on the accuracy of such estimates.

Where’s the Government Plan?

A search of public records and official statements yields no evidence of a government strategy to address the water shortage in time for the summer—despite expectations of a promising tourist season. The situation recalls the 2014 water crisis, when Lebanon considered importing water from Turkey by ship—a proposal met with ridicule, especially since Lebanon was negotiating to export water to Cyprus just a year earlier.

With limited time and options, here are ten practical measures the government could implement:

Introduce water rationing to preserve supplies throughout the summer.

Launch public awareness campaigns on water conservation.

Impose penalties for all forms of water wastage.

Repair the pipeline network and modernize infrastructure using World Bank loans.

Encourage rooftop rainwater harvesting to maximize use of seasonal rainfall.

Curb agricultural irrigation waste, which accounts for around 60% of water demand, and switch to efficient drip irrigation systems.

Protect freshwater springs from pollution and seek funding to build sewage systems, especially near water sources.

Promote water recycling for non-potable uses in industry and agriculture.

Invest in seawater desalination, if the crisis deepens.

Develop a national water management plan focused on sustainable long-term access to potable water.

Solving Lebanon’s water crisis will ultimately require major infrastructure investments and a complete overhaul of how the country manages its natural resources.

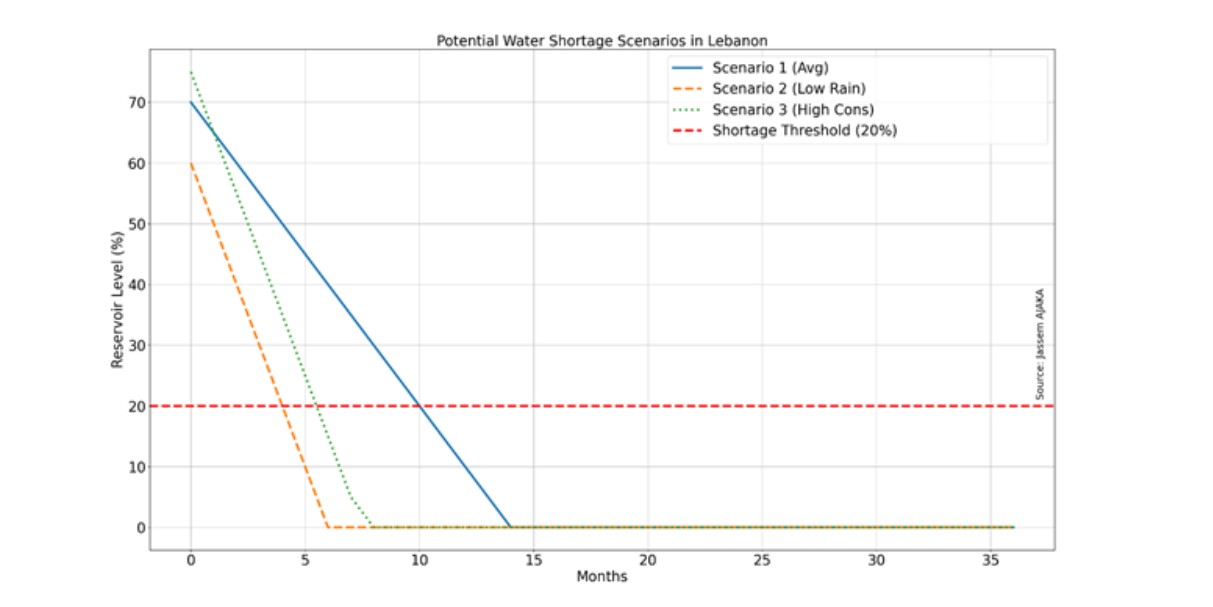

How long will the water reserve last?

Answering that question isn’t easy. There’s no clear data on how much water is currently stored or how much demand will rise in the summer months. However, simple modeling based on a few assumptions provides some insight.

Three variables were considered:

Storage capacity as a percentage of total volume

Average monthly rainfall as a percent of capacity

Monthly water usage, including household, industrial, and agricultural consumption

Three scenarios were simulated:

Average rainfall and consumption

Below-average rainfall

Above-average summer consumption

The model did not account for evaporation or leakage, which would worsen the outlook.

Chart 1, based on these scenarios, shows Lebanon could face a severe water shortage in as little as four months (worst case) or as long as ten months (best case). Either way, the findings underscore the urgent need for the Lebanese government to take immediate, decisive action—or risk a full-blown crisis.

Please post your comments on:

[email protected]

Politics

Politics